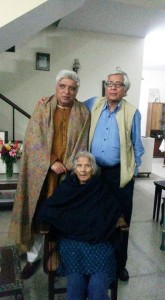

Amma: Remembering Hamida Salim (1922–2015)

On 16 August 2015, Mrs Hamida Salim left for her heavenly abode, leaving behind her family and a remarkable collection of her literary work. She authored five books in Urdu, translated in Hindi and contributed literary articles about her brother Asrarul Haq Majaz, a renowned Urdu poet.

Mrs Salim was also the first female postgraduate in Economics from Aligarh Muslim University. Interestingly, her elder sister, Safia Akhtar, mother of noted Urdu poet, lyricist and writer Javed Akhtar and Salman Akhtar was the first undergraduate from the same university.

Most people lose height with age and become shorter. My aunt, Hamida Salim, who passed away earlier this week, defied this conventional reality. As she grew older, she gained stature, became taller in everyone’s eyes. Fine-boned and increasingly frail though she was, Amma (as I called her), retained a zest for life till the very end. This past Eid-ul-Fitr saw her enthusiastically enjoying the arrival of friends, family members and acquaintances alike. On countless evenings, when the ‘regulars’ among her physician daughter’s circle gathered for a drink or two in Amma’s cozy living room, she was an eager, if abstaining, participant in the lively goings-on. The tantalising arc between the sacred glow of Eid and electrified evenings of fine whisky and heated conversation constitutes the fascinating and rich sojourn of her life.

Born in 1922 in Rudauli, a small village near Lucknow, Amma was the youngest daughter of a feudal young man, Siraj-ul-Haq, who was intent not only upon gaining higher education for himself but, after moving to the nearby big city, also upon facilitating the intellectual growth of his children. Four of them ended up becoming illustrious figures of letters and political praxis in modern Indian history: Asrar-ul-Haq Majaz (the poet, often referred to as the Keats of India), Ansar Harvani (the youthful freedom fighter who later served many terms as MP), Safia Akhtar (the renowned litterateur and author of the finest personal correspondence since Ghalib) and Hamida Salim, economist, educator, chef-par-excellence, raconteur, keeper of family secrets, writer, great sister and mother, an unforgettable wife and above all, benefactor to numerous souls in need, including an orphan like me. “Come and be fed” was writ large on the door of her heart.

The canvas of Amma’s life was grand, with eras and epochs unfolding in Lucknow, Aligarh, Pune, Khartoum, Addis Ababa, London, San Francisco and her last abode, New Delhi. While her chosen field of study was economics, Amma turned into a memoirist of formidable stature after a long career in academia. Recording her family history, the lives of her siblings, and her own travels across the globe was not a vehicle for nostalgic self-indulgence for her. It was a pathway to the simultaneous celebration and deconstruction of personal, familial, and cultural myths. It was a gift of empathy and knowledge to her reader who gained instant familiarity with what was distant in time and space. Yes, she offered ample ‘aesthetic bribe’, to use Freud’s designation of the pleasure generated by a creative writer but, in the end, her literary output was a testimony to how time impacts upon our inner and outer lives and upon culture-at-large.

Her diction was quintessentially ‘Hindustani’, her tone a blend of earthiness and optimism. She offered hope, which is a twin of love, to her readers. And, she bestowed love, which is a twin of hope, upon her children and grandchildren and also upon the entire clan of Salims, Shiblis, Ahmads, Harvanis, Farids, and even a few Akhtars.

A particular memory involving her comes to mind. To be sure, it seems strange to recount this one as opposed to many memories of her direct acts of kindness towards me. But being a psychoanalyst and a poet, I trust my unconscious to not lead me astray at this revered moment of extoling my aunt’s matter-of-fact tenderness toward all whose life she touched. This happened some three or four years ago. I was sitting in her living room, talking with her about this or that – frankly, I do not remember what. The two of us were alone in the room. Suddenly the front door opened and a tall, lanky man walked in. Amma kept her attention on what I was saying and was not perturbed by the intrusion at all. The man walked up to her, bowed, touched her feet and then taking the staircase in the living room, quickly went upstairs and all but vanished. No longer used to such unscheduled and unexpected arrivals to one’s house, I, an Americanised doctor in his mid-60s, asked Amma: “Who is this guy?” She told me that the man was a surgeon who came over a couple of times during the day to smoke a cigarette on her upstairs balcony since the hospital, (on the campus of which Amma lived with her physician daughter) did not permit smoking. Then she told me to continue with my narrative. What struck me was the calm with which she reacted to the intrusion, the grace with which she bore this man’s touching her feet, the equanimity with which she accepted his need to smoke, and the ease with which she sustained her attention towards me. In Winnicott’s terms, she ‘held’ both me and the surgeon. And it is this large-hearted maternal fortitude which I salute now, as I remember my beloved aunt who died a few days ago. Died, yes, in external reality. But in the inner reverie of my wonder and gratitude, she will live forever.

(Salman Akhtar, MD, is Professor of Psychiatry at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. An author or editor of over 70 books on diverse topics in psychiatry and psychoanalysis, he is also an established poet in both Urdu and English languages.)